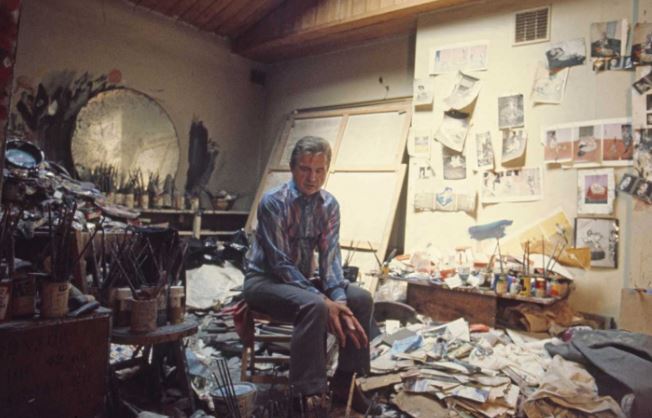

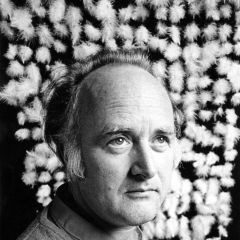

Artist of the Week: Henk Peeters (1925 – 2013)

“The world is going to change radically.” Henk Peeters said so more than once, as an expression of his deep desire for a Communist society. It was not to be, but Peeters remained an idealist. Today, he is best known for his mixed-media works constructed from natural elements, tactile industrial materials, and found objects, which he made as an active member of the radical Dutch Nul group.

Before Peeters took this important place in Dutch cultural life in the 1960s and his position within the Zero movement, he grew up in a communist environment. His father had a leading position in the CPN (the Dutch Communist Party), and as a young boy, Peeters read the USSR Im Bau, a propaganda magazine for the Soviet Union which was designed by the Russian artist El Lissitzky and printed with constructivist photomontages . Peeters himself made illustrations for the illegal communist party newspaper De Waarheid. Stimulated by his parents, he started his art education at the Eerste Nederlandse Vrije Studio in The Hague. In 1941, he entered the Royal Academy of Art in the same city, where he was taught by Rein Draijer (1899-1986), Willem Schrofer (1898-1968), Willem Rozendaal (1899-1971), and in his first year by Paul Citroen (1896-1983). To escape compulsory labor service, Peeters had to go into hiding in 1943, and during this period, he and other students were taught at home. He was most in touch with Schrofer, with whom he shared his artistic and political interests.

During these years, Peeters worked mainly in a figurative style, and through his teachers, he was introduced to the work and ideas of constructivists and the artists of Der Blaue Reiter. He immersed himself in the Bauhausbücher, and at Schrofer’s home he saw work by Piet Mondrian and Friedrich Vordemberge-Gildewart, among others. In line with what he saw and stimulated by Scrofer, Peeters started making abstract paintings around 1944. His first abstract compositions show a complex structure of straight and curved lines in different colors that intersect in various places.

For a short year, Peeters left for Paris, where he focused on the role of abstraction in socialist art. In Paris he painted himself in a realistic style, in which he tried to depict the sad, hopeless situation of the post-war years as purely as possible. When he returned to the Netherlands, making art was put on the back burner so that he could devote more time to his family; in 1948, Peeters married Truus Nienhuis, with whom he had three sons. Between 1953 and 1955, he worked temporarily as a creative therapist in the psychiatric university clinic of Leiden and he worked for the pedagogical department of the Gemeente Museum in The Hague.

After meeting Bram Bogart (1921-2012) in 1957, Peeters style began to shift radially, with the emphasis in his art shifting more and more to the material. He used thick layers of paint, textiles, plaster, and so on. Together with Armando (1929-2018), Kees van Bohemen (1928-1985), Jan Schoonhoven (1914-1994), and Jan Henderikse (1937), he formed the Dutch Informal Group. His art became increasingly monochrome and immaterial, and he made his first ‘pyrographies’: fire-scorched and intoxicated canvas, foam rubber, or plastic. This kind of work can be regarded as the first step in the direction it took in 1961, when he founded the Nul Group together with Armando and Schoonhoven.

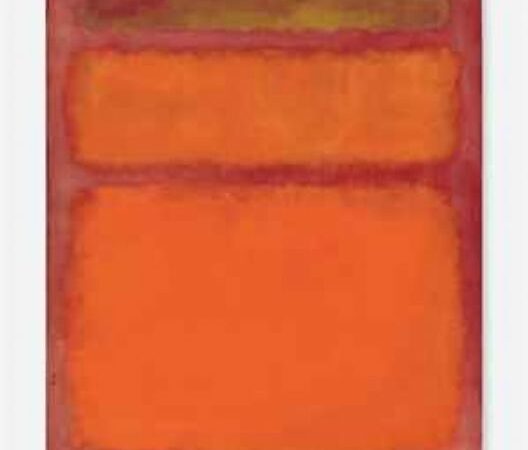

This Nul Group was a collective of Dutch artists who manifested themselves between 1961 and 1966 and felt kinship with the international ZERO movement that had started in Düsseldorf. They shared a quest for a new objectivity in art, which was all about eliminating the artist’s personal style and elevating everyday life to art through the use of ordinary materials. Peeters did this by making the viewer conscious of their environment while bringing sensitive consciousness-raising. The materials he chose for his art frequently had a tactile appeal while also creating a certain untouchability; for example, he stuck candle tapers behind plastic foil or placed mesh in front of cotton wool. Through these, often white, works, he was visually closely related to the German ZERO artists. There was also a clear relationship with Nouveau Realisme; Peeters used ready-mades, which he bought in inexpensive stores and isolated in the work of art. In these, he had a preference for modern, clean, industrial materials, such as plastic and nylon. He once said, “With my work, I have always wanted it to look just as fresh as if it was in the HEMA (the Dutch chain store). It must not be artified… I had no need for artistic cotton wool. ” Peeters also worked with natural processes, such as light and water reflections, with ice, rain, snow, and mist. Art and life should be joined together inextricably, and thus, in 1961, Henk Peeters became a work of art himself when Piero Manzoni (1933-1963) appointed him as one; this was certified and signed by the Italian artist.

Together with the other Nul group artists, Peeters shared the common dedication to banishing personal expression and painting composition-free works. This resulted in Nul’s first major event in the Netherlands when Peeters organized the exhibition Nul at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, which took place in 1962. The exhibition presented a broad overview of the international ZERO movement, including artists from France, Italy, Germany, Switzerland , and Belgium. In addition to various exhibitions in Düsseldorf, Paris, and Milan, another museum exhibition at the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague followed in 1964. The exhibition ZERO-0-NUL featured works by Armando, Henk Peeters, and Jan Schoonhoven, along with works by the German ZERO artists Heinz Mack (1993), Otto Piene (1928-2014), and Günther Uecker (1930). In 1965, Peeters organized the exhibition zero nineteen hundred and sixty five in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, in which artists from the Japanese Gutai group participated, along with European ZERO artists. As in Nul62, Nul65 also displayed the broad visual spectrum and the international reach of the ZERO movement, including artists’ collectives such as Azimut from Milan and ZERO from Düsseldorf, as well as the New York-based Yayoi Kusama and American artist George Rickey. “Nul intends to signify a new start, more an idea and a climate than a particular style or form; it aims to abandon all that no longer has any viability, even the painting, if need be. The artist takes a step back; communal ideas inspire virtually anonymous works that have little in common with traditional art. What emerges are objects, vibrations, structures, and reflections… Not the banality of everyday life, nor simply the regularities of optical phenomena. Zero is the domain between “Pop” and “Op,” or, to paraphrase Otto Piene: the quarantine zero, the quiet before the storm, the phase of calm and resensitization.” With these words, Henk Peeters introduced the catalog of the exhibition zero nineteen hundred and sixty five.

The various artists’ collectives organized their own exhibitions and produced their own publications, in which they took a stand against the established order. They wanted to break with existing structures and institutions and displayed an unconditional optimism about the possibilities of technological progress. That also meant that exhibitions no longer had to take place in museums. Artists produced objects with modern industrial materials, such as plastic, aluminium, and everyday objects, like light bulbs and engines, and created total installations using sound, light, and motion. The planned but never realized project Zero op Zee (Zero on Sea), which should have taken place in 1966 on the Scheveningen Pier, was an ultimate expression of their optimism about the possibilities of technology and their dedication to integrating art into everyday reality. At the same time, Zero on Sea marked the end of the movement. From then on, each artist subsequently went their own way, remaining true to the movement’s principles, striking out in new directions, or giving up art production (for a time).

In all publications about Zero, attention is paid to the great significance that Peeters has had for this international movement, both as an organizer and curator of a number of important Zero exhibitions, but also for his role as an artist. His art, as well as his choice of materials and personal philosophy, is underlain by a deep-rooted democratic principle. The socialist ideals inculcated in him during his childhood are a major motivation for all his activities—of which there have been many.

Source: veilinghuisaag.com