Andy Warhol, and his importance in art

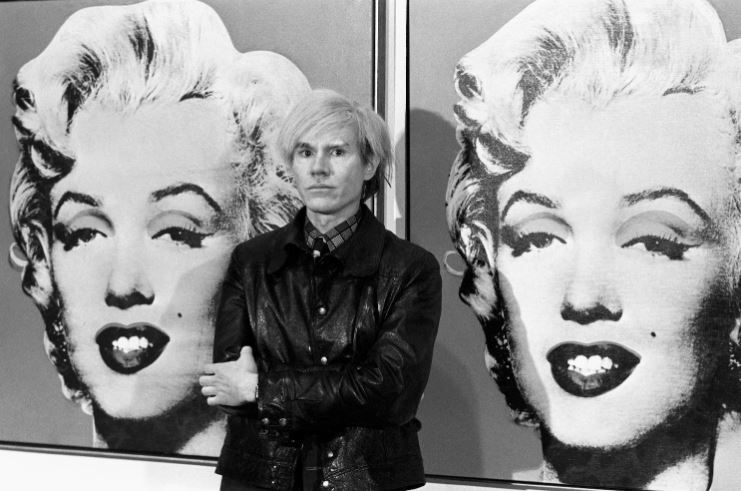

The number of artists who are household names is vanishingly small. But near the top of this list is a first-generation American born in Pittsburgh to a blue-collar family of Slovakian immigrants: Andrew Warhola, aka Andy Warhol (1928–1987). Warhol was a prime mover of Pop Art, and though he didn’t invent the genre, he possessed a unique insight into its implications, due partly to his own story.

Warhol came of age just as the WASP elite that had held the country in its grip since the days of the founders was being pushed aside for a meritocracy led primarily by the offspring of formerly marginalized ethnic groups from southern and eastern Europe—people, in other words, like him. Consciously or not, in his work he intuited how these changes reflected the displacement of high art by the divertissements of comic books, movies, television, and advertising. He also connected the centrifugal dynamic of this new egalitarianism to late capitalism, recognizing how both destabilized conventional hierarchies of wealth and status. (He once said of Coca-Cola, “A Coke is a Coke, and no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking.”)

In other words, he foresaw our current neoliberal order. He likewise anticipated the disposable nature of our social media–addled present (“In the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes”) and the triumph of money as the final arbiter of quality (“Business is the best art”).

Warhol’s adopted persona as a bewigged enigma could be construed, perhaps, as both a reenactment of the social transformations noted above and a shrewd strategy. (“I learned that you actually have more power when you shut up” is how he put it.) But his cosplaying also constituted a sort of hiding in plain sight, best summed up in Warhol’s most famous remark about himself: “If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.”

So, while his biographical details are concrete enough, Warhol remains a cipher.

Early Life

Andy Warhol, Be a Somebody with a Body, 1985–1986, acrylic and silkscreen ink on linen, 16 x 20 inches.

Photo : The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. Copyright © 2022 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

His father was a coal miner whose death when Warhol was 14 so traumatized him that he hid under his bed instead of attending the funeral. His mother, Julia, had an interest in drawing and painting, which she passed to her son.

At eight, Warhol came down with chorea, a movement disorder involving involuntary jerking of the face, shoulders, and hips. Forced to stay home from school, he distracted himself with magazines. His illness left him with a blotchy complexion and a lifelong insecurity about his looks that manifested as an equally enduring fascination with glamour.

Warhol grew up gay and Catholic at a time when neither was acceptable in Protestant America. (His religion played a large role in his work, however much it’s been minimized by critics and historians, but more on that later.)

He graduated from high school with honors and attended the prestigious Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University). And before he became famous, he earned a living as a graphic designer, successful enough to afford a townhouse on the Upper East Side of Manhattan where he and Julia resided.

The Commercial Artist

Andy Warhol, In the Bottom of My Garden, 1958, ink and Dr. Martin’s aniline dye on Strathmore paper, 23 x 14 7/8 inches.

Photo : The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. Copyright © 2022 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Warhol came to New York to pursue a career in commercial art, landing his first professional gig drawing shoes for Glamour magazine in the late 1940s. He later created album covers for Columbia records and became the in-house artist for the footwear manufacturer Israel Miller.

During this time, he developed a technique of blotting ink renderings before they dried, leaving peculiar dotted lines, and used tracing paper to reproduce his designs. Warhol owed an unlikely debt to the Depression-era Social Realist and committed leftist Ben Shahn, whom he’d been aware of since art school. He emulated the older artist so faithfully that clients would say employing Warhol was like hiring Shahn on the cheap—minus the pinko baggage.

First Gallery Show

Andy Warhol, Back of Seated Male, 1950s, ballpoint pen on Manila paper, 16 1/2 x 13 3/4 inches.

Photo : The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. Copyright © 2022 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In tandem with his illustration work, Warhol was making his own art, which he began to exhibit in 1952 with a solo show at the Hugo Gallery in New York. Four years later, he appeared in a group show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, followed by another one-man outing at Bodley Gallery, in 1957. While still indebted to Shahn, this work was often overtly homoerotic, with depictions of beautiful young men and close-up views of male genitalia. Many of the images were based on photos that Warhol copied with an opaque projector.

Warhol wasn’t the only postwar figure who supported himself through commercial art: James Rosenquist had been a billboard painter, and both Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg did window dressing. But Warhol carried the ethos of commercial art into his practice: He treated his collectors as clients, took direction from his dealers, and readily accepted ideas suggested by others.

He made no characterological distinction between the assembly line and his studio, which he would later name the Factory. There he reprised the production process that took commercial assignments from drawing table to printing press.

Soup Cans

Andy Warhol, Campbell’s Soup Cans, (1962), installation view, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 13 November 2020.

Photo : Cindy Ord/Getty Images

Warhol made his initial Pop Art forays between 1960 and 1962 with paintings based on newspaper images including ads, comic strips, and front-page headlines. Most of these were done in black and white or as grisailles, though several sourced from the funny pages were in color. Subject-wise, they ranged from mundane circulars for appliances (Icebox, 1961) to tragic tabloid covers (129 Die in Jet!, 1962), and together they conveyed the way mass media brought all content to the same level.

In April 1961, Warhol unveiled these paintings in the window of the upscale department store Bonwit Teller. By then, borrowing everyday artifacts and images in art had become common, starting with Cubist collage and the “Readymade” conceit of Marcel Duchamp. Early Modernists in America such as Stuart Davis, Charles Demuth, and Gerald Murphy had incorporated elements of signage and product packaging into their paintings. And two tiny postwar collages—one by Kurt Schwitters, the other by Richard Hamilton—pointed the way to Pop Art, with the former’s inclusion of a comic strip panel and the latter’s incorporation of a bodybuilder holding a Tootsie Pop.

More directly, Warhol’s work was preceded by the flags and targets of Johns and the sidewalk-harvested combines of Rauschenberg. He also contended with contemporaries such as Rosenquist, Claes Oldenburg, and especially Roy Lichtenstein, whose comic-book paintings rivaled his own. But two specific developments would vault Warhol over the pack.

The first of these was his Campbell’s Soup cans, which debuted at Los Angeles’s Ferus Gallery in 1962. Numbering 32, one for each variety of soup, they were lined up on shelves, supermarket style. Except for using a stamp for part of the label, Warhol painted each by hand. The result directly linked fine art to consumerism.

Silkscreen Paintings

Andy Warhol, Silver Car Crash (Double Disaster) (1963) on display at Sotheby’s auction house in New York, 1 November 2013.

Photo : Emmanuel Dunand/AFP via Getty Images

Duplicating images manually proved arduous, so Warhol turned to his second innovation: photo silk-screening. By exposing positive film enlargements of newspaper or magazine clippings to screens covered in a light-sensitive emulsion, he produced stencils fine enough to print halftone patterns. Besides boosting Warhol’s output to a state beyond prodigious, the effect created an immediate sensation.

Warhol recognized that Hollywood, no less than Campbell’s, cranked out merchandise in the form of celebrities, so he switched from soup to stars. After experiments involving Warren Beatty and teen heartthrob Troy Donahue, he produced his best-known piece after the soup cans: Gold Marilyn Monroe (1962), a headshot of the blonde bombshell set Madonna-like against a gilded field. Warhol also limned flat areas of color below the silkscreen layer, which became a signature trope. So did the repeating and overlapping of imagery first introduced in the “Silver Elvis” series (taken from a still of the singer as a cowpoke drawing his six-shooter) that constituted his second Ferus show, in 1963.

Warhol produced multiple iterations of Marilyn and other leading ladies like Elizabeth Taylor but turned to darker themes as well. His treatments of a veiled Jackie Kennedy at JFK’s burial directly referred to her husband’s assassination in 1963. Death wasn’t a new topic for Warhol, but it was given its most profound expression in his so-called “Disasters.” Echoing the social turmoil following the president’s murder, the “Disasters” consisted of 70 paintings grouped into subsets featuring race riots, car crashes, and, most notoriously, electric chairs. These were reproduced in meandering grids across monochrome backdrops whose bright hues (orange, lavender) were a jarring contrast to the imagery. Like Warhol’s 129 Die in Jet!, the “Disasters” spoke to the ubiquity of violence in the news and our deadened reaction to it.

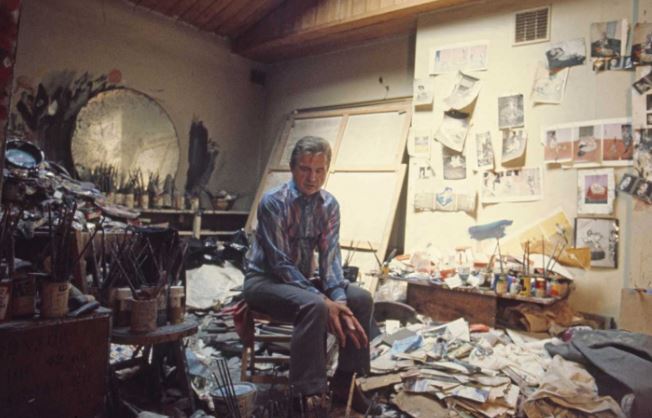

The Factory

Andy Warhol at the Factory with posters for Tub Girls (1967) and Lonesome Cowboys (1968).

Photo : Jack Mitchell/Getty Images

Ever obsessed with Tinseltown, Warhol transformed the Factory into a downtown simulacrum of the studio system. He produced his own movies, cultivating a roster of “superstars” from the ranks of hangers-on who took advantage of the studio’s open-door policy to party and revel in Warhol’s shadow. (The Factory, which had four different locations between 1963 and 1987, also became a magnet for other artists, musicians, and assorted beautiful people.)

While Warhol codirected and commercially released full-length features like Chelsea Girls, his most notable filmic accomplishments were deconstructions of the medium focused on static subjects—the most impassive of which was the Empire State Building, captured for eight hours in Empire. Sleep, another film nearly as long, starred Warhol’s lover at the time, the poet John Giorno, as he slumbered.

Warhol also became a rock-and-roll impresario, promoting the Velvet Underground, who were given new instruments and rehearsal space at the Factory (where they performed at all-night parties presided over by Andy). Warhol designed their first album cover (which displayed his name instead of the band’s and depicted a banana that could be peeled back to reveal a pink interior) and staged multimedia spectacles, called the Exploding Plastic Inevitable, highlighted by the Velvets and featuring film projections and light shows.

Near-Death and the End of the ’60s

Andy Warhol, Brillo Boxes (1964), installation view, Tate Gallery, London, 16 February 1971.

Photo : Central Press/Getty Images

Concurrent with Pop Art’s emergence during the 1960s was the rise of Minimalism, whose practitioners cultivated a reductively abstract approach, devising artworks so devoid of associations that they were labeled “specific objects” instead. These forms were also produced serially and mounted as installations meant to engage with the space around them. As an indication of what Warhol may have thought of Minimalist aesthetics, some of his works—stacks of identical copies of Brill-O Soap cartons, and rooms plastered with cow wallpaper or filled with floating mylar balloons—parodied them.

The 1960s represented Warhol’s most inventive period, but an event near the decade’s end decisively altered his life and career. On June 3, 1968, Valerie Solanas, a self-styled radical feminist who held a grudge against Warhol for supposedly stealing the manuscript for a play she wrote, entered his office and shot him point-blank. Two bullets tore through his stomach, liver, spleen, esophagus, and lungs, and at one point he was declared dead before being revived. He spent two months in the hospital undergoing a grueling sequence of operations that left him wearing a surgical corset for the remainder of his life.

Later Career

Andy Warhol, Shadows (1978–79), installation view, Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, 25 February 2016.

Photo : Ander Gillenea/AFP via Getty Images

The repercussions of Warhol’s being shot were immediate: he closed the Factory to outsiders and embarked on what he called “Business Art.” Under that aegis, he produced society portraits as well as print editions, and launched a variety of other commercial ventures, including cable television shows and Interview magazine. He also licensed his name for products ranging from soap to Jell-O molds (he apparently drew the line at bedsheets).

This transformation in the way he managed his affairs was a logical extension of a respect for marketing that dated back to his days as a commercial artist. And it provided a template for future entrepreneur/artists like Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, Banksy, and Kaws, who operate both within and without the art world.

At the same time, Warhol continued to produce significant paintings, such as his multipart Shadow painting, his “Mao” and “Skulls” series, and his “Oxidation” works, for which his assistants urinated on copper-coated canvases that consequently revealed splashes of green patina. Warhol, then, was hardly out of ideas, but to outsiders, and often to insiders as well, it seemed that more than ever, his legend was overtaking his art.

During the 1980s, Warhol hung out with the young Warhol manqués Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, doing collaborative projects with the latter. He also created a body of hand-painted compositions of borrowed ads that recalled his efforts from the early ’60s. But he arguably saved the biggest surprise for last with his final cycle of paintings based on Leonardo’s Last Supper, which finally laid bare the religious impulse that had always informed his art.

The Last Supper

Andy Warhol, The Last Supper (The Big C) (1986), installation view in the exhibition “Repent and Sin No More,” Cloister of Bramante, Rome, 29 September 2006.

Photo : Andreas Solaro/AFP via Getty Images

Raised in the Byzantine Catholic Church, Warhol was taken to mass by his mother as a child and continued to go as an adult. He underwrote his nephew’s priesthood studies and served meals to the homeless in keeping with Church teachings on helping the poor.

More pertinently for his art, his faith was tied to the traditions of Eastern Christianity—among them the veneration of icons, which threw his efforts into a different light. Gold Marilyn, for example, is usually seen as an ironic comment on how pop culture has become a substitute for religion, but Warhol understood that worshipping a star in image form was no different from doing the same for Christ; indeed, unlike Judaism’s and Islam’s prohibitions against depicting God, the Church transformed Jesus into a logo for the divine.

Based on a 19th-century engraving of Leonardo’s masterpiece for the refectory of the Santa Maria delle Grazie convent in Milan, Warhol’s Last Supper was commissioned for an exhibit by the dealer Alexander Iolas, whose Milan gallery stood across the street from the convent. Warhol attended the exhibition’s opening on January 22, 1987. Exactly one month later, he died at New York–Presbyterian Hospital following the removal of an infected gall bladder, one of the long-term complications stemming from the attempt on his life.

It’s somewhat chilling to consider that Warhol’s Last Supper may have represented a premonition of his own death. In any case, he wound up where he began, in Pittsburgh, buried under a headstone that he thought should be left blank, or at least inscribed with only one word: Figment. In the end, Andy Warhol was a construct of Andrew Warhola’s imagination that remains firmly lodged in our own.

Source: BY HOWARD HALLE